|

Black Sailors in the RCN

Breaking the Colour Barrier

Who was the the first Black man to join the RCN, RNCVR, RCNVR or RCNR? That will likely be a tough question to answer.

The crew photo below for HMCS PATRIOT, received from the Naval Museum of Halifax, has one crew member that appears to be black. PATRIOT was in service in the RCN from 1920 to 1929. While initially stationed in Esquimalt - she transferred to Halifax in 1921. The sailor in question, circled in red, is wearing an RCNVR cap tally. The CO centre of the front row is Lt George Clarence Jones - this puts the photo between 03 Sep 1922 and 23 Aug 1923. The name of this sailor is unknown.

The sailor in question is indicated by a red circle Click on the above photo to view a larger image

At some point after the above photo of the crew of HMCS PATRIOT was taken .... up until and during the Second World War, the RCN would not recruit Black men to serve in its ranks. The official reason was that when majority and minority groups come together, the minority group would suffer. When Black men tried to join the Navy, they were refused and directed to join the Army. This worked well for the RCN until 1942 when a young man named Piercey Augustus Haynes, a British subject of British Guyana descent, went to the recruiting office in Winnipeg to join the Navy.

The following is a excerpt from parliamentary records of 10 Mar 1999 from a statement given in the house by Hon. Calvin Woodrow Ruck (Enlistment into Royal Canadian Navy - The Black Experience-Inquiry)

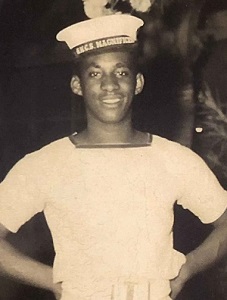

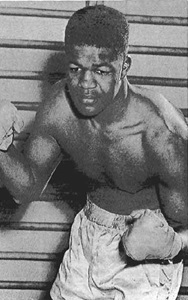

"An incident took place in Winnipeg, Manitoba, involving a young black man named Piercey Haynes. He had come to Canada, specifically to Winnipeg, many years earlier with his parents, from British Guiana. He was well known and well thought of in Winnipeg. In high school, he was a boxer, and in 1942 he decided he wanted to go into the navy, for the simple reason that he saw many of his friends and former schoolmates flocking into the navy. For some reason, many people in Western Canada chose the navy as the service they wanted to join. Some people say that the reason for this is that westerners were freshwater sailors and they wanted to find out what this saltwater business was all about.

Piercey Haynes, along with many others, went to the recruiting station. He walked in and spoke to the officer in charge, a captain in rank, who refused to accept him into the navy and suggested he join the army. Piercey Haynes replied that, if he was not good enough for the navy, he was not good enough for the army. He continued his protests by writing a letter to the Naval Secretary, the late Honourable Angus L. Macdonald, a fellow Nova Scotian and fellow Cape Bretonner. Mr. Macdonald got back to him by mail and indicated to him that that clause in the Naval Service Act was put there in the best interests of minority persons. He indicated that long research had proven that, when a minority group and a majority group come together, the minority group suffers.

Piercey Haynes did not accept that line of reasoning. He was going into the navy. There would be officers there to make sure all members of the navy were treated equally. He persisted and continued to write letters, and the Naval Council met on several occasions in an attempt to deal with the issue. Finally, they decided to revise the Naval Service Act by removing that clause and opening the navy to Canadians of good health, regardless of race, colour or creed. The only people who could not get in at that point in time were, of course, females. That has changed now to some degree.

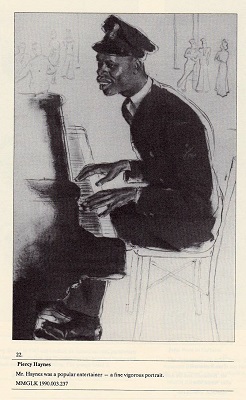

Piercey Haynes made further contact with Angus L. Macdonald, who instructed him to go back to the naval station. He returned armed with a letter from Mr. Macdonald. The captain in charge, the same gentleman, refused even to look at the letter. That was insubordination. Shortly thereafter, that captain was removed from that post and Piercey Haynes went into the navy. He spent four or five years of wartime service in the navy. For some reason, he never went to sea. He spent considerable time in Halifax, where he was a musician, and he spent time entertaining other servicemen. By the time the war ended, four or five other blacks had entered the Royal Canadian Navy."

Additional reading: A False Sense of Equality: The Black Canadian Experience of the Second World War

|