|

For Posterity's

Sake

For Posterity's

Sake

A Royal

Canadian Navy Historical Project

Heroes

and History

Makers of the RCN

|

Bernays, Max, CPO

Brooke, Margaret

Martha, LCdr, RCN

Dube, Rachel Mari-Anna

(nee Richard) (aka Mama Camille)

Gray, Robert, Lt, VC

Harrison Brothers

Hose, Rear-Admiral Walter

Kingsmill, Admiral Sir Charles Edmund

|

Landymore, Rear-Admiral

William (Bill) Moss

Maitland-Dougall,

William, Lt

Ng Muk Kah, B.E.M. (aka Jenny of Jenny's Side Party, Hong Kong)

Paddon, Stuart Edmund,

Rear-Admiral

Sherwood, Frederick

Henry, LCdr

Stubbs, John Hamilton,

LCdr

|

|

|

Rear-Admiral

Walter Hose

Born with sea salt in his blood, Hose had two good reasons for joining

the Royal Canadian Navy. The first was the opportunity for promotion,

and the second had everything to do with making an impact on the young

service. After transferring from the Royal Navy to the RCN in 1911, he

rose to become Director of Naval Service by 1921, a position he held

for 13 years, through five different cabinet ministers. Under his

guidance, the navy built its plans around what the government would

support, established a nationwide footprint through the reserve

system, built a tough little fleet of destroyers and established a

clearer vision of itself, supported by smart policy. In short, he laid

the groundwork for the navy as it prepared for the Second World War.

Restore

the Honour- Walter

Hose, Father and Saviour of the RCN

This

monument is dedicated to the memory of Rear-Admiral Walter Hose, whose final

resting place lies immediately to your right. It was his vision, personal

efforts and steadfast dedication to the fledgling Naval Service of Canada,

in it's time of greatest need, which saved the future Royal Canadian Navy.

Perhaps most significant was his dream of the "Citizen Sailor", a

concept that led to the birth of the modern day Naval Reserve, an

organization that now proudly stretches from cost to coast and whose 24

divisions are represented by the crests emblazoned around the base of this

monument. Rightly recognized as the "Father of the Naval Reserve",

he will never be forgotten.

Erected

in Honour of Rear-Admiral Walter Hose through the joint efforts of Her

Majesty's Canadian Ship Hunter, The Royal Canadian Naval Association,

The Naval Association of Canada and the Navy League of Canada.

Dedicated here, with the kind permission of Heavenly Rest Cemetery, on

22 June 2014. Photo

of the monument courtesy of Phil Beausoleil

|

|

|

|

Admiral

Sir Charles Edmund Kingsmill, CMG, RN

Admiral

Kingsmill was born in Guelph, Canada West in 1855, and joined the

Royal Navy (RN) as a Cadet in 1869. After an illustrious carrier in

the RN, he retired as as Rear-Admiral in September 1908. In May of

1908 he was appointed Commander Canadian Fishery Protection Service

and later Director Marine Services of the Department of Marine and

Fisheries (Canada). In May 1910 he became the first Director of the

Naval Service of Canada and subsequently was promoted to Vice-Admiral

on the RN Retired List in 1913. Admiral Kingsmill was promoted to his

current rank, on the RN retired list, in April 1917. He continued to

serve as Director of the Naval Service until his departure in 1920. He

died 15 August 1935.

Admiral

Sir Charles Edward Kingsmill

|

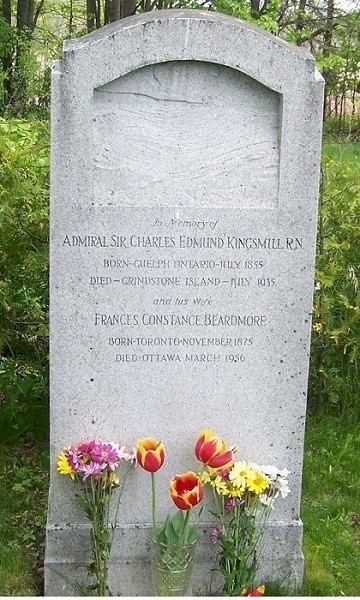

Headstone

of Admiral Sir Charles Edmund Kingsmill |

A memorial in

honour of Admiral Kingsmill and his service to the fledgling RCN (right) |

Courtesy

of Peter Clarabut, CPO2, RCN

Double

click on the photos to view a larger image

|

|

|

|

Rear-Admiral

William (Bill) Moss Landymore

Decorated

in wartime after two ships were sunk under him, he rose to the top of the RCN

only to defy Ottawa's plan to integrate the military. As a result, he lost his

job, but won the hearts of the rank and file Two decades after he fought the

German and Japanese navies during the Second World War, Rear Admiral Bill

Landymore threw himself into the battle of his life when he took on the

government of Canada in an epic struggle that transfixed the nation. It

was arguably the most controversial defence issue in Canadian history and Rear

Adm. Landymore, who at 50 could have served five more years, had gone down

guns blazing in the best naval tradition. In two years, the RCN's six senior

admirals had been retired prematurely or fired. Generals and air marshals had

also left.

Click

here to read the MARGEN sent by Rear-Admiral Landymore on his final day in

the RCN

|

|

|

|

Lt

Robert Gray, VC, RCNVR

British

Columbia's Robert Gray was a member of the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer

Reserve who was serving as a pilot with the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm in

the Far East. He earned a Victoria Cross in the final weeks of the Second

World War for his actions on August 9, 1945. On that day, Gray attacked a

Japanese warship and was hit by heavy

anti-aircraft fire. Despite the damage, Lieutenant Gray continued his attack

and scored a direct hit on the Japanese escort vessel Amakusa, sinking it.

Sadly, Gray did not survive. Photo: Department of National Defence.

Source: Canadian

Virtual War Memorial

At

age 25 he'd been awarded the Victoria Cross, Distinguished Service Cross,

39-45 Star, Atlantic Star, Africa Star, Pacific Star, Defense Medal,

Canadian Volunteer Service Medal with Overseas Bar, War Medal with Mentioned

in Dispatches Oak Leaf.

|

|

|

|

Lt

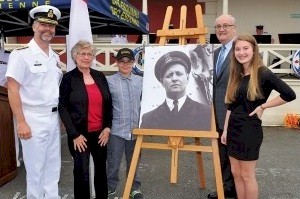

William Maitland-Dougall, RCN

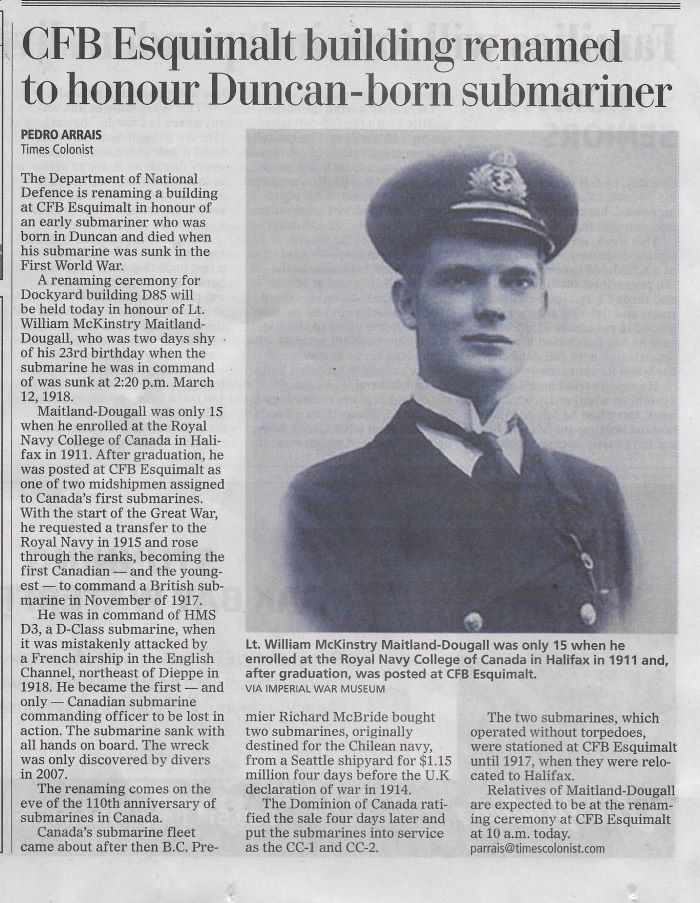

Lt

William Maitland-Dougall, RCN - Canada's only submarine commanding officer

lost in action

On

March 7, 1918, Lt. Maitland-Dougall, RCN, took D3 to patrol off Le Havre,

France. He was in high spirits – it would be a short patrol and he would be

ashore in time to celebrate his 23rd birthday. But D3 did not return. What

happened was not revealed to the grieving relatives of the crew until several

years later. Bombs dropped by a French airship on March 12 sank D3 – the

French had not known the Allied submarine recognition signals. Maitland-Dougall

and his crew fought to save her but she was lost with all hands. (British

divers located the wreck of D3 in 2007.) The Royal Canadian Navy has never

officially recognized the accomplishments of Lt. Maitland-Dougall, RCN, then

or now. Indeed, few modern submariners have even heard his name. Maitland-Dougall

was the first and only Canadian submarine commanding officer to be lost in

action. He also remains the youngest to earn command. (Source: CFB

Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum)

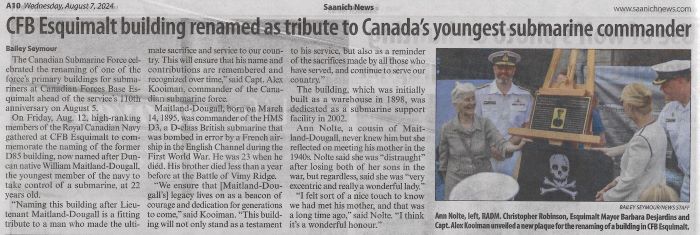

Article from the Victoria Times Colonist

02 Aug 2024

Article from the Saanich News 07 Aug 2024

|

|

|

|

Rear-Admiral

Stuart Edmund Paddon, RCNVR, RCN

Paddon was a member of HMS Prince of Wales crew

during the Battle of the Denmark Straight and fatal encounter with

Japanese aircraft near Malaya.

The

RCNVR provided a small but important role for the Royal Navy's early

Radar Systems.

May 27,

1941: The German battleship Bismarck is sunk. Several days earlier,

Canadian officer Stuart Paddon was witness to one of the most

infamous encounters in naval history - the Battle of the Denmark

Strait on May 24. Paddon, then just a sub lieutenant in the RCNVR,

was the radar officer on board HMS Prince of Wales, the brand new

British battleship assigned along with HMS Hood to sink the

Bismarck.

Paddon

was in charge of the Prince of Wales' many radar systems - ten, the

most numerous on any warship to date. In the early days of the war,

radar remained somewhat of a mystery to many - its concepts often

misunderstood and technical expertise even rarer. Thus, the Royal

Navy (RN) had a difficult time finding suitable officers to operate

them. This was compounded by the fact that the Royal Air Force had

taken most of the home talent to operate their systems watching

British skies.

Paddon

and his classmates were in the final year of their undergraduate

Physics degree at the University of Western Ontario (UWO) in

September 1939. That school year, an unusual curriculum was offered

to them by the department head, one that focused on electronics. At

the time, electronics was a subject for post-graduate courses, not

undergrad. As it turned out, the RN was somewhat desperate for

expertise and had approached the RCN about the matter, which in turn

passed it on to the National Research Council, and thence to the

universities in Canada. In 1940, Paddon and his cohort, now with

some electronics training, enlisted and were sent across the

Atlantic.

But

back to May 24: Paddon, sitting in the room responsible for the

Prince of Wales' Type 281 radar, was monitoring the chase against

the Bismarck. Clear on his screen were three contacts: Bismarck, the

heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, and a third supply ship. Dutifully, he

relayed the coordinates of the enemy ships to the Prince of Wales'

gunnery controllers. However, due to the lack of practice on the

part of the ship's crew, the gunnery controllers did not take note

of Paddon's information. Using traditional optical means, the Prince

of Wales nevertheless managed to score hits on the Bismarck...but

not before HMS Hood was hit and sunk with only three survivors. It

is impossible to know whether better adherence to Paddon's radar

information could have saved the Hood. Meanwhile, the chase wore on,

and Paddon's only information about the battle was through his radar

screen, on which he could actually see the radar reflections coming

from Bismarck's 15" shells flying through the air.

Paddon

would continue to serve on the Prince of Wales until that ship's

demise at the hands of Japanese bombers off Malaya in December 1941.

Paddon was fortunate to have survived that sinking and was rescued

by one of the escorting destroyers. He spent some months at Ceylon

as the Port's Radar Officer, repairing incoming vessels' radar

systems, before returning to Canada. During his duty in Ceylon, he

noted that many British warships' radar officers were his old

classmates from UWO, or were at least Canadian - a small but crucial

role often forgotten in history. Paddon continued to serve in the

Royal Canadian Navy until retiring in 1972 with the rank of Rear

Admiral.

Courtesy of John Hawley

Original source of this article is unknown

|

|

|

Larry,

Thomas, Gordon, Clifford and Arthur Harrison

Born

in Picton, Ontario, the Harrison brothers all joined the Royal Canadian Navy;

the only known occasion where 5 brothers served in the RCN at the same

time. In

the left photo, in happier times Harrison brothers are all wearing their

square rig. In the right hand photo, after unification, they came together as

pallbearers for their father's funeral.

|

|

|

|

CPO

Max Bernays, RCNR

Max

Bernays (January 3, 1910 - March 30, 1974) was a Royal Canadian Naval

Reserve Acting Chief Petty Officer who fought in the Battle of the Atlantic

during the Second World War. He was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal

for his actions aboard HMCS Assiniboine on August 6, 1942.

On

August 6, 1942, the Assiniboine engaged the German U-Boat U-210. A fierce

gun-battle ensued, causing a major fire aboard the Assiniboine.

Lieutenant-Commander John H. Stubbs, commander of the Assiniboine,

maneuvered the vessel to ram the U-Boat. Bernays ordered his telegraph

operators who were giving orders to the engine room to leave, as the fire

began to surround the wheelhouse. Bernays manned the helm and did the work

of the two telegraph operators while Stubbs gave orders to ram U-210. As

the gun battle grew in intensity, Assiniboine rammed U-210 abaft of her

conning tower, crippling the submarine. 38 of the 48 German crew were

rescued. Assiniboine's losses were minimal, with one killed and 13 wounded.

Bernays

was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal for his heroic actions. His

actions displayed such a degree of courage that Rear Admiral L.W. Murray

recommended him for the Victoria Cross. Rear Admiral L.W. Murray believed that

"the manner in which this comparatively young rating remained at his

post, alone, and carried out the 133 telegraph orders as well as the many helm

orders necessary to accomplish the destruction of this submarine, whilst the

wheelhouse was being pierced by explosive shell from the enemy's Oerlikon gun

and his only exit was cut off by fire, is not only in keeping with the highest

traditions of the Service but adds considerably to those traditions. I am

proud of the privilege to recommend Acting Chief Petty Officer Bernays for the

Victoria Cross." The

RCN's Honours and Awards Committee considered Murray's recommendation and

confirmed his selection of Bernays for the VC. However, United Kingdom

authorities decided that the recommendation did not come up to the standard

usually required for the Victoria Cross, and awarded him the Conspicuous

Gallantry Medal instead. On

25 May 2015, the Associate Minister of National Defence announced that the 3rd

Arctic Offshore Patrol ship will be named HMCS Max Bernays. Crowsnest

Magazine Man of the Month, Jul 1954 - CPO2 Bernays - Page

1, Page 2

(Left)

A portrait of Chief Petty Officer (CPO) Max Bernays is unveiled during the

naming announcement of the third Arctic/Offshore Patrol Ship, held at the CFB

Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum. (L-R) Rear Admiral Bill Truelove, Commander Maritime Forces Pacific/Joint Task

Force (Pacific); Marilyn Bernays, daughter-in-law of CPO Bernays; Max

Thompson, great-grandson of CPO Bernays; Julian Fantino, Associate Minister of

National Defence; and Carly Bernays, great-granddaughter of CPO Bernays. LS

Ogle Henry, MARPAC Imaging Services (Right)

CPO Max Bernays' awards and decorations held at the Canadian War Museum |

|

|

|

LCdr

Frederick Henry Sherwood, DSC w/Bar, RCNVR

A

native of Ottawa, Fred Sherwood joined the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer

Reserve in 1933 and was one of 27 Canadians who volunteered for service in

British submarines during World War Two.

In

1940, Fred Sherwood and J. D. Woods were the first two Canadian Naval

Reservists to take the submarine officer training course. On completion, they

were offered a choice of postings - home waters (North Atlantic) or the

Mediterranean. They flipped for it, and Freddie ended up staying home while

his classmate shipped out to Alexandria, Egypt. As it turns out, J. D. Woods

made one particularly unpleasant patrol and decided submarines were not for

him.

LCdr

Sherwood served as Watchkeeping Officer in HMS SEALION from 1940 to August

1941; as First Lieutenant in HMS L23 from August 1941 to January 1942; and as

First Lieutenant in HMS P211 (later renamed SAFARI) from January to November

1942. It was while operating in the Mediterranean around Malta that he was

awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for "courage and skill in

successful submarine patrols".

In

December, 1942, he completed the legendary 'Perisher' - the Royal Navy

Submarine Command Course so named because it had a failure rate of 40-60%.

Pass, and you were guaranteed to get a submarine command. Fail, and you were

immediately returned to surface ships never to see the inside of a submarine

again. On graduation, he became Commanding Officer of HMS P556 (aka 'The

Reluctant Dragon', because frequently she didn't want to dive!), from March to

June 1943, then CO of HMS SPITEFUL from July 21, 1943 to July 24, 1946.

Under

his command, SPITEFUL completed the three longest patrols for a S-boat at the

time, sinking multiple Japanese ships. By April, 1945, SPITEFUL had bombarded

installations on the Andaman Islands and Christmas Island. "Just to keep

them on their toes."

Fred,

and his future wife Mary (herself a cipher clerk at Allied Headquarters in

Burma), married in Santiago, Chile in 1947 and spent many happy decades

together.

In

2010, a dinner was held for Canadian Perisher graduates and submarine CO's.

There, LCdr Fred Sherwood sat across from LCdr Alex Kooiman - the oldest and

newest Canadian Perisher graduates, sixty-five years apart. In July, 2011, the

Victoria Submarine Command Team Trainer, part of the Canadian Forces Naval

Operations School in Halifax, Nova Scotia, was named after him. In the words

of CANFLTLANT at the time, Commodore Larry Hickey, himself a graduate of

Perisher, "We honour a fine submarine officer who was tested in war, and

who delivered the goods. The Command Team Trainer named in his honour ensures

that Fred Sherwood will not be forgotten by the Navy writ large, and more

importantly, by the Canadian submarine community."

On

the 14th of May, 2013, Fred Sherwood passed away peacefully in Ottawa,

Ontario. In the words of his son, Tim Sherwood - "He was many things to

many people during his life, but he was always a submariner in his

heart." (Source/Credit: The

Submariners Association of Canada)

|

|

|

|

Rachel

Mari-Anna Dube (Richard) 1918 - 2009

The

name probably means nothing to most people. However, if you were in the Royal

Canadian Navy (or its post 1968 permutations) any time after 1948, there is a

very good chance you met Rachel at some point in your service.

Rachel

lived in Halifax and ran a little operation just outside RCN barracks, HMCS

Stadacona. And while most sailors in the RCN eventually passed through

barracks at Stadacona, most of those sailors also ended up in Rachel's little

restaurant, just two blocks away from the main gate.

You

see, to us sailors, Rachel was better known as Momma Camille and she served

the best fish & chips in Halifax. She was known as The woman who fed the

fleet and many a Saturday night run ashore in in "Slackers" ended at

Momma Camille's Fish & Chips.

Momma

Camille retired in 1984 although the name of her fish & chip shop can be

seen all over Nova Scotia.

She

passed on at age 90 on 22 May this year. Many a retired and serving sailor

will be hoisting a glass in thanks to Rachel for saving us from the fare of

"A" Block in "Stad".

Fair

winds and following seas, Momma Camille. (Source: Article from unknown

newspaper - 26 May 2009)

Click

here to read newspaper articles and letters of thanks to Mama Camille

|

|

|

|

Ng

Muk Kah, B.E.M. (1917 - 2009)

Generations

of sailors who visited Hong Kong will mourn the death of Jenny. She was a much

loved living legend who, for all the colony’s constant change, remained the

same incomparable institution for over half a century.

Much

of her life was an enigma. However. the authors of her twenty-seven Certificates

of Service generally agreed that she was born in a sampan in Causeway Bay in

1917. Her mother, Jenny One, according to her one surviving Certificate of

Service, which was copied in 1946 from an older, much battered and largely

illegible document, ‘provided serviceable sampans for the general use of the

Royal Navy, obtained sand, and was useful for changing money‘. She brought up

her two daughters to help her.

Behind

her perpetual great gold-toothed grin Jenny complained; ‘I velly chocker. All

time work in sampan, no learn to lead or lite.’ But what she lacked in

education she made up more than a hundredfold with her immense and impressive

experience in ship husbandry, her unfailing thoroughness and apparently

inexhaustible energy, her unquestionable loyalty and integrity, her infectious

enthusiasm and her innate cheerfulness.

Officially,

Jenny’s Date of Volunteering was recorded as 1928. From then until 1997, when

the colony became a Special Administrative Region of China and the Royal Navy

moved out, she and her team of tireless girls, who at one time numbered nearly

three dozen, unofficially served the Royal and Commonwealth Navies in Hong Kong

by cleaning and painting their ships, attending their buoy jumpers, and, dressed

in their best, waiting with grace and charm upon their guests at cocktail

parties. Captains and Executive Officers would find fresh flowers in their

cabins and newspapers delivered daily. And many a departing officer received a

generous gift as a memento from Jenny. For all of this, she steadfastly refused

ever to take any payment. Instead she and her Side Party earned their keep

selling soft drinks to the ships’ companies and accepting any item of scrap

which could be found on board.

Most

treasured of all Jenny’s distinctions was the British Empire Medal awarded her

in the Hong Kong Civilian List of the Queen’s Birthday Honours in 1980 and

with which she, formally named Mrs. Ng Muk Kah, was invested by the Governor of

Hong Kong, Sir Murray MacLehose.

In

later years, Hong Kong was no longer visited by the great fleets of battleships

and cruisers which gave Jenny and her Side Party their livelihood and she found

it increasingly difficult to make ends meet. Yet she stayed fit and was always

willing to undertake any work available.

Jenny

died peacefully in Hong Kong on Wednesday 18th February 2009. She was 92 years

old. (Source: Naval

Historical Society of Australia)

- Chief

and Petty Officers' Association (Esquimalt) newsletter Bulletin" article on Jenny's Side party - Page

1 Page

2

|

|

|

|

Margaret Martha Brooke, LCdr, RCN,

Canadian naval hero

Photo of Margaret Brooke courtesy of Department of National

Defence

Margaret Martha Brooke (BHSC'35, BA'65, PhD'71), a

palaeotologist and Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) Nursing Sister decorated for

gallantry in combat during the Second World War, died on January 9, 2016 in

Victoria, B.C. at the age of 100 years.

On April 13, 2015 the Government of Canada announced that

an Arctic/Offshore Patrol Ship (AOPS) would be named after Brooke, who holds

degrees from the U of S College of Home Economics and the Department of

Geological Sciences at the College of Arts & Science. She is the author of

several papers in the field of palaeontology.

On October 14, 1942, during a crossing of the Cabot Strait

off the coast of Newfoundland, the ferry SS Caribou was torpedoed by the German

submarine U-69. The ferry sank in five minutes. Fighting for her own survival,

Lieutenant-Commander (LCdr) Brooke also did everything humanly possible to save

the life of her colleague and friend, Nursing Sister Sub-Lieutenant Agnes Wilkie,

while both women clung to ropes on a capsized lifeboat. In spite of Brooke’s

heroic efforts to hang on to her with one arm, her friend succumbed to the

frigid water.

For this selfless act, Brooke was named a member (Military

Division) of the Order of the British Empire.

The HMCS Margaret Brooke will be the second of six Harry

DeWolf-class AOPS constructed as part of Canada's National Shipbuilding

Procurement Strategy. Construction began in 2015.

Brooke grew up in the small farming community of Ardath, SK

during the Depression. Her mother was determined that her daughter would attend

university so, in 1933, she moved to Saskatoon to attend the University of

Saskatchewan.

After earning a BHSC in 1935, she joined the Royal Canadian

Navy in 1942. She was serving as a Nursing Sister in the RCN hospital in HMCS

Stadacona, Halifax, NS, when the fateful ferry incident occurred.

After she retired from the RCN in 1962, she returned to

Saskatoon and the University of Saskatchewan where she earned a BA and then a

PhD in biostratigraphy and micro-palaeontology. She remained in the Department

of Geological Sciences as an instructor and research associate until her

retirement in 1986.

Vice-Admiral Mark Norman, Commander of the Royal Canadian

Navy, issued a statement on behalf of the RCN and the Canadian Armed Forces on

the passing of Lieutenant-Commander (ret’d) Brooke, calling her a “true

Canadian naval hero.”

Government of Canada news release

|

HOME PAGE SHIP INDEX

CONTACT

|